Windsor Castle, parts of which date back to the 11th century, is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. The castle is notable for its long association with the British royal family and for its architecture. The original castle was built after the Norman invasion by William the Conqueror. Since the time of Henry I, it has been used by succeeding monarchs and it is the longest-occupied palace in Europe. The castle’s lavish, early 19th-century State Apartments are architecturally significant, described by art historian Hugh Roberts as “a superb and unrivalled sequence of rooms widely regarded as the finest and most complete expression of later Georgian taste”. The castle includes the 15th-century St George’s Chapel, considered by historian John Robinson to be “one of the supreme achievements of English Perpendicular Gothic” design. More than five hundred people live and work in Windsor Castle.

Originally designed to protect Norman dominance around the outskirts of London, and to oversee a strategically important part of the River Thames, Windsor Castle was built as a motte and bailey, with three wards surrounding a central mound. Gradually replaced with stone fortifications, the castle withstood a prolonged siege during the First Barons’ War at the start of the 13th century. Henry III built a luxurious royal palace within the castle during the middle of the century, and Edward III went further, rebuilding the palace to produce an even grander set of buildings in what would become “the most expensive secular building project of the entire Middle Ages in England”. Edward’s core design lasted through the Tudor period, during which Henry VIII and Elizabeth I made increasing use of the castle as a royal court and centre for diplomatic entertainment.

Windsor Castle survived the tumultuous period of the English Civil War, when it was used as a military headquarters for Parliamentary forces and a prison for Charles I. During the Restoration, Charles II rebuilt much of Windsor Castle with the help of architect Hugh May, creating a set of extravagant, Baroque interiors that are still admired. After a period of neglect during the 18th century, George III and George IV renovated and rebuilt Charles II’s palace at colossal expense, producing the current design of the State Apartments, full of Rococo, Gothic and Baroque furnishings. Victoria made minor changes to the castle, which became the centre for royal entertainment for much of her reign. Windsor Castle was used as a refuge for the royal family during the bombing campaigns of the Second World War and survived a fire in 1992. It is a popular tourist attraction, a venue for hosting state visits, and the Queen’s preferred weekend home.

Windsor Castle occupies a large site of more than thirteen acres (five hectares), and combines the features of a fortification, a palace, and a small town. The present-day castle was created during a sequence of phased building projects, culminating in the reconstruction work after a fire in 1992. It is in essence a Georgian and Victorian design based on a medieval structure, with Gothic features reinvented in a modern style. Since the 14th century, architecture at the castle has attempted to produce a contemporary reinterpretation of older fashions and traditions, repeatedly imitating outmoded or even antiquated styles. As a result, architect Sir William Whitfield has pointed to Windsor Castle’s architecture as having “a certain fictive quality”, the Picturesque and Gothic design generating “a sense that a theatrical performance is being put on here”, despite late 20th century efforts to expose more of the older structures to increase the sense of authenticity. Although there has been some criticism, the castle’s architecture and history lends it a “place amongst the greatest European palaces”.

At the heart of Windsor Castle is the Middle Ward, a bailey formed around the motte or artificial hill in the centre of the ward. The motte is 50 ft (15 m) high and is made from chalk originally excavated from the surrounding ditch. The keep, called the Round Tower, on the top of the motte is based on an original 12th-century building, extended upwards in the early 19th century under architect Jeffry Wyattville by 30 ft (9 m) to produce a more imposing height and silhouette. [9] The interior of the Round Tower was further redesigned in 1991–3 to provide additional space for the Royal Archives, an additional room being built in the space left by Wyattville’s originally hollow extension. The Round Tower is in reality far from cylindrical, due to the shape and structure of the motte beneath it. The current height of the tower has been criticised as being disproportionate to its width; archaeologist Tim Tatton-Brown, for example, has described it as a mutilation of the earlier medieval structure.

The western entrance to the Middle Ward is now open, and a gateway leads north from the ward onto the North Terrace. The eastern exit from the ward is guarded by the Norman Gatehouse. This gatehouse, which in fact dates from the 14th century, is heavily vaulted and decorated with carvings, including surviving medieval lion masks, traditional symbols of majesty, to form an impressive entrance to the Upper Ward. Wyattville redesigned the exterior of the gatehouse, and the interior was later heavily converted in the 19th century for residential use.

The Upper Ward of Windsor Castle comprises a number of major buildings enclosed by the upper bailey wall, forming a central quadrangle. The State Apartments run along the north of the ward, with a range of buildings along the east wall, and the private royal apartments and the King George IV Gate to the south, with the Edward III Tower in the south-west corner. The motte and the Round Tower form the west edge of the ward. A bronze statue of Charles II on horseback sits beneath the Round Tower. Inspired by Hubert Le Sueur’s statue of Charles I in London, the statue was cast by Josias Ibach in 1679, with the marble plinth featuring carvings by Grinling Gibbons. The Upper Ward adjoins the North Terrace, which overlooks the River Thames, and the East Terrace, which overlooks the gardens; both of the current terraces were constructed by Hugh May in the 17th century.

Traditionally the Upper Ward was judged to be “to all intents and purposes a nineteenth-century creation … the image of what the early nineteenth-century thought a castle should be”, as a result of the extensive redesign of the castle by Wyattville under George IV. The walls of the Upper Ward are built of Bagshot Heath stone faced on the inside with regular bricks, the gothic details in yellow Bath stone. The buildings in the Upper Ward are characterised by the use of small bits of flint in the mortar for galletting, originally started at the castle in the 17th century to give stonework from disparate periods a similar appearance. The skyline of the Upper Ward is designed to be dramatic when seen from a distance or silhouetted against the horizon, an image of tall towers and battlements influenced by the picturesque movement of the late 18th century. Archaeological and restoration work following the 1992 fire has shown the extent to which the current structure represents a survival of elements from the original 12th-century stone walls onwards, presented within the context of Wyattville’s final remodelling.

The State Apartments form the major part of the Upper Ward and lie along the north side of the quadrangle. The modern building follows the medieval foundations laid down by Edward III, with the ground floor comprising service chambers and cellars, and the much grander first floor forming the main part of the palace. On the first floor, the layout of the western end of the State Apartments is primarily the work of architect Hugh May, whereas the structure on the eastern side represents Jeffry Wyattville’s plans.

The interior of the State Apartments was mostly designed by Wyattville in the early 19th century. Wyattville intended each room to illustrate a particular architectural style and to display the matching furnishings and fine arts of the period. With some alterations over the years, this concept continues to dominate the apartments. Different rooms follow the Classical, Gothic and Rococo styles, together with an element of Jacobean in places. Many of the rooms on the eastern end of the castle had to be restored following the 1992 fire, using “equivalent restoration” methods – the rooms were restored so as to appear similar to their original appearance, but using modern materials and concealing modern structural improvements. These rooms were also partially redesigned at the same time to more closely match modern tastes. Art historian Hugh Roberts has praised the State Apartments as “a superb and unrivalled sequence of rooms widely regarded as the finest and most complete expression of later Georgian taste.” Others, such as architect Robin Nicolson and critic Hugh Pearman, have described them as “bland” and “distinctly dull”.

A photograph of a large room with a long red carpet stretching through the middle of it and windows on the right hand side. Furniture fills both sides of the room. The ceiling contains ornate plasterwork and a chandelier hangs down from the middle of the picture.

The Crimson Drawing Room in 2007 following the 1992 fire and subsequent remodelling

Wyattville’s most famous work is the rooms designed in a Rococo style. These rooms take the fluid, playful aspects of this mid-18th-century artistic movement, including many original pieces of Louis XV decoration, but project them on a “vastly inflated” scale. Investigations after the 1992 fire have shown though that many Rococo features of the modern castle, originally thought to have been 18th-century fittings transferred from Carlton House or France, are in fact 19th-century imitations in plasterwork and wood, designed to blend with original elements. The Grand Reception Room is the most prominent of these Rococo designs, 100 ft (30 m) long and 40 ft (12 m) tall and occupying the site of Edward III’s great hall. This room, restored after the fire, includes a huge French Rococo ceiling, characterised by Ian Constantinides, the lead restorer, as possessing a “coarseness of form and crudeness of hand … completely overshadowed by the sheer spectacular effect when you are at a distance”. The room is set off by a set of restored Gobelins French tapestries. Although decorated with less gold leaf than in the 1820s, the result remains “one of the greatest set-pieces of Regency decoration”. The White, Green and Crimson Drawing Rooms include a total of sixty-two trophies: carved, gilded wooden panels illustrating weapons and the spoils of war, many with Masonic meanings. Restored or replaced after the fire, these trophies are famous for their “vitality, precision and three-dimensional quality”, and were originally brought from Carlton House in 1826, some being originally imported from France and others carved by Edward Wyatt. The soft furnishings of these rooms, although luxurious, are more modest than the 1820s originals, both on the grounds of modern taste and cost.

Wyattville’s design retains three rooms originally built by Hugh May in the 17th century in partnership with the painter Antonio Verrio and carver Grinling Gibbons. The Queen’s Presence Chamber, the Queen’s Audience Chamber and the King’s Dining Room are designed in a Baroque, Franco-Italian style, characterised by “gilded interiors enriched with florid murals”, first introduced to England between 1648–50 at Wilton House. Verrio’s paintings are “drenched in medievalist allusion” and classical images. These rooms were intended to show an innovative English “baroque fusion” of the hitherto separate arts of architecture, painting and carving.

Two designs for a ceiling; one showing a side view of structure and decoration; the bottom showing how it would appear from below. The ceiling is decorated with a network of gothic arches in gold on a blue background.

A handful of rooms in the modern State Apartments reflect either 18th-century or Victorian Gothic design. The State Dining Room, for example, whose current design originates from the 1850s but which was badly damaged during the 1992 fire, is restored to its appearance in the 1920s, before the removal of some of the gilded features on the pilasters. Anthony Salvin’s Grand Staircase is also of mid-Victorian design in the Gothic style, rising to a double-height hall lit by an older 18th-century Gothic vaulted lantern tower called the Grand Vestibule, designed by James Wyatt and executed by Francis Bernasconi. The staircase has been criticised by historian John Robinson as being a distinctly inferior design to the earlier staircases built on the same site by both Wyatt and May.

Some parts of the State Apartments were completely destroyed in the 1992 fire and this area was rebuilt in a style called “Downesian Gothic”, named after the architect, Giles Downes. The style comprises “the rather stripped, cool and systematic coherence of modernism sewn into a reinterpretation of the Gothic tradition”. Downes argues that the style avoids “florid decoration”, emphasising an organic, flowing Gothic structure. Three new rooms were built or remodelled by Downes at Windsor. Downes’ new roof of St George’s Hall is the largest green-oak structure built since the middle Ages, and is decorated with brightly coloured shields celebrating the heraldic element of the Order of the Garter; the design attempts to create an illusion of additional height through the gothic woodwork along the ceiling. The Lantern Lobby features flowing oak columns forming a vaulted ceiling, imitating an arum lily. The new Private Chapel is relatively small, only able to fit thirty worshippers, but combines architectural elements of the St George’s Hall roof with the Lantern Lobby and the stepped arch structure of the Henry VIII chapel vaulting at Hampton Court. The result is an “extraordinary, continuous and closely moulded net of tracery”, complementing the new stained glass windows commemorating the fire, designed by Joseph Nuttgen. The Great Kitchen, with its newly exposed 14th-century roof lantern sitting alongside Wyattville’s fireplaces, chimneys and Gothic tables, is also a product of the reconstruction after the fire.

The ground floor of the State Apartments retains various famous medieval features. The 14th-century Great Under croft still survives, some 193 ft (60 m) long by 31 ft (9 m) wide, divided into thirteen bays. At the time of the 1992 fire, the under croft had been divided into smaller rooms; the area is now opened up to form a single space in an effort to echo the under crofts at Fountains and Rievaulx Abbeys, although the floor remains artificially raised for convenience of use. The “beautifully vaulted” 14th-century Larderie passage runs alongside the Kitchen Courtyard and is decorated with carved royal roses, marking its construction by Edward III.

The Lower Ward lies below and to the west of the Round Tower, reached through the Norman Gate. Originally largely of medieval design, most of the Lower Ward was renovated or reconstructed during the mid-Victorian period by Anthony Salvin and Edward Blore, to form a “consistently Gothic composition”. The Lower Ward holds St George’s Chapel and most of the buildings associated with the Order of the Garter.

On the north side of the Lower Ward is St George’s Chapel. This huge building is the spiritual home of the Order of the Knights of the Garter and dates from the late 15th and early 16th century, designed in the Perpendicular Gothic style. The ornate wooden choir stalls are of 15th-century design, having been restored and extended by Henry Emlyn at the end of the 18th century, and are decorated with a unique set of brass plates showing the arms of the Knights of the Garter over the last six centuries. On the west side, the chapel has a grand Victorian door and staircase, used on ceremonial occasions. The east stained glass window is Victorian, and the oriel window to the north side of it was built by Henry VIII for Catherine of Aragon. The vault in front of the altar houses the remains of Henry VIII, Jane Seymour and Charles I, with Edward IV buried nearby. The chapel is considered by historian John Robinson to be “one of the supreme achievements of English Perpendicular Gothic” design.

A close-up photograph of a building made with black timbers and red brick. The building has four tall, brick chimneys. A relatively modern drainpipe comes down the middle of the building.

The Horseshoe Cloister, built in 1480 and reconstructed in the 19th century

At the east end of St George’s Chapel is the Lady Chapel, originally built by Henry III in the 13th century and converted into the Albert Memorial Chapel between 1863–73 by George Gilbert Scott. Built to commemorate the life of Prince Albert, the ornate chapel features lavish decoration and works in marble, glass mosaic and bronze by Henri de Triqueti, Susan Durant, Alfred Gilbert and Antonio Salviati. The east door of the chapel, covered in ornamental ironwork, is the original door from 1246.

At the west end of the Lower Ward is the Horseshoe Cloister, originally built in 1480, near to the chapel to house its clergy. It houses the vicars-choral or lay clerks of the chapel. This curved brick and timber building is said to have been designed to resemble the shape of a fetlock, one of the badges used by Edward IV. George Gilbert Scott heavily restored the building in 1871 and little of the original structure remains. Other ranges originally built by Edward III sit alongside the Horseshoe, featuring stone perpendicular tracery. As of 2011, they are used as offices, a library and as the houses for the Dean and Canons.

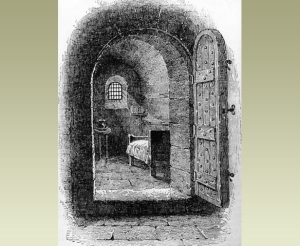

Behind the Horseshoe Cloister is the Curfew Tower, one of the oldest surviving parts of the Lower Ward and dating from the 13th century. The interior of the tower contains a former dungeon, and the remnants of a sally port, a secret exit for the occupants in a time of siege. The upper storey contains the castle bells placed there in 1478, and the castle clock of 1689. The French-style conical roof is a 19th-century attempt by Anthony Salvin to remodel the tower in the fashion of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc’s recreation of Carcassonne.

On the opposite side of the chapel is a range of buildings including the lodgings of the Military Knights, and the residence of the Governor of the Military Knights? These buildings originate from the 16th century and are still used by the Knights, who represent the Order of the Garter each Sunday. On the south side of the Ward is King Henry VIII’s gateway, which bears the coat of arms of Catherine of Aragon and forms the secondary entrance to the castle.

Windsor Castle was originally built by William the Conqueror in the decade after the Norman conquest of 1066. William established a defensive ring of motte and bailey castles around London; each was a day’s march – about 20 miles (32 km) – from the city and from the next castle, allowing for easy reinforcements in a crisis. Windsor Castle, one of the rings of fortifications, was strategically important because of its proximity to both the River Thames, a key medieval route into London, and Windsor Forest, a royal hunting preserve previously used by the Saxon kings. The nearby settlement of Clivore, or Clewer, was an old Saxon residence. The initial wooden castle consisted of a keep on the top of a man-made motte, or mound, protected by a small bailey wall, occupying a chalk inlier, or bluff, rising 100 ft (30 m) above the river. A second wooden bailey was constructed to the east of the keep, forming the later Upper Ward. By the end of the century, another bailey had been constructed to the west, creating the basic shape of the modern castle. In design, Windsor most closely resembled Arundel Castle, another powerful early Norman fortification, but the double bailey design was also found at Rockingham and Alnwick Castle.

Windsor was not initially used as a royal residence; the early Norman kings preferred to use the former palace of Edward the Confessor in the village of Old Windsor. The first king to use Windsor Castle as a residence was Henry I, who celebrated Whitsuntide at the castle in 1110 during a period of heightened insecurity. Henry’s marriage to Adela, the daughter of Godfrey of Louvain, took place in the castle in 1121. During this period the keep suffered a substantial collapse – archaeological evidence shows that the southern side of the motte subsided by over 6 ft (2 m). Timber piles were driven in to support the motte and the old wooden keep was replaced with a new stone shell keep, with a probable gateway to the north-east and a new stone well. A chemise, or low protective wall, was subsequently added to the keep.

Henry II came to the throne in 1154 and built extensively at Windsor between 1165 and 1179. Henry replaced the wooden palisade surrounding the upper ward with a stone wall interspersed with square towers and built the first King’s Gate. The first stone keep was suffering from subsidence, and cracks were beginning to appear in the stonework of the south side. Henry replaced the keep with another stone shell keep and chemise wall, but moved the walls in from the edge of the motte to relieve the pressure on the mound, and added massive foundations along the south side to provide additional support. Inside the castle Henry remodelled the royal accommodation. Bagshot Heath stone was used for most of the work, and stone from Bedfordshire for the internal buildings.

King John undertook some building works at Windsor, but primarily to the accommodation rather than the defences. The castle played a role during the revolt of the English barons: the castle was besieged in 1214, and John used the castle as his base during the negotiations before the signing of the Magna Carta at nearby Runnymede in 1215. In 1216 the castle was besieged again by baronial and French troops under the command of the Count of Nevers, but John’s constable, Engelard de Cigogné, successfully defended it.

The damage done to the castle during the second siege was immediately repaired in 1216 and 1221 by Cigogne on behalf of John’s successor Henry III, who further strengthened the defences.[78] The walls of the Lower Ward were rebuilt in stone, complete with a gatehouse in the location of the future Henry VIII Gate, between 1224 and 1230. Three new towers, the Curfew, Garter and the Salisbury towers were constructed. The Middle Ward was heavily reinforced with a southern stone wall, protected by the new Edward III and Henry III towers at each end.

Windsor Castle was one of Henry’s three favourite residences and he invested heavily in the royal accommodation, spending more money at Windsor than in any other of his properties. Following his marriage to Eleanor of Provence, Henry built a luxurious palace in 1240–63, based around a court along the north side of the Upper Ward. This was intended primarily for the queen and Henry’s children. In the Lower Ward, the king ordered the construction of a range of buildings for his own use along the south wall, including a 70 ft (21 m) long chapel, later called the Lady Chapel. This was the grandest of the numerous chapels built for his use, and comparable to the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris in size and quality. Henry repaired the Great Hall that lay along the north side of the Lower Ward, and enlarged it with a new kitchen and built a covered walkway between the Hall and the kitchen. Henry’s work was characterised by the religious overtones of the rich decorations, which formed “one of the high-water marks of English medieval art”. The conversion cost more than £10,000. The result was to create a division in the castle between a more private Upper Ward and a Lower Ward devoted to the public face of the monarchy. Little further building was carried out at the castle during the 13th century; the Great Hall in the Lower Ward was destroyed by fire in 1296, but it was not rebuilt.

Edward III was born at Windsor Castle and used it extensively throughout his reign. In 1344 the king announced the foundation of the new Order of the Round Table at the castle. Edward began to construct a new building in the castle to host this order, but it was never finished. Chroniclers described it as a round building, 200 ft (61 m) across, and it was probably in the centre of the Upper Ward. Shortly afterwards, Edward abandoned the new order for reasons that remain unclear, and instead established the Order of the Garter, again with Windsor Castle as its headquarters, complete with the attendant Poor Knights of Windsor. As part of this process Edward decided to rebuild Windsor Castle, in particular Henry III’s palace, in an attempt to construct a castle that would be symbolic of royal power and chivalry. Edward was influenced both by the military successes of his grandfather, Edward I, and by the decline of royal authority under his father, Edward II, and aimed to produce an innovative, “self-consciously aesthetic, muscled, martial architecture”.

Edward placed William of Wykeham in overall charge of the rebuilding and design of the new castle and whilst work was ongoing Edward stayed in temporary accommodation in the Round Tower. Between 1350 and 1377 Edward spent £51,000 on renovating Windsor Castle; this was the largest amount spent by any English medieval monarch on a single building operation, and over one and a half times Edward’s typical annual income of £30,000. Some of the costs of the castle were paid from the results of ransoms following Edward’s victories at the battles of Crécy, Calais and Poitiers. Windsor Castle was already a substantial building before Edward began expanding it, making the investment all the more impressive, and much of the expenditure was lavished on rich furnishings. The castle was “the most expensive secular building project of the entire Middle Ages in England”.

Edward’s new palace consisted of three courts along the north side of the Upper Ward, called Little Cloister, King’s Cloister and the Kitchen Court. At the front of the palace lay the St George’s Hall range, which combined a new hall and a new chapel. This range had two symmetrical gatehouses, the Spicerie Gatehouse and the Kitchen Gatehouse. The Spicerie Gatehouse was the main entrance into the palace, whilst the Kitchen Gatehouse simply led into the kitchen courtyard. The great hall had numerous large windows looking out across the ward. The range had an unusual, unified roof-line and, with a taller roof than the rest of the palace, would have been highly distinctive. The Rose Tower, designed for the king’s private use, set off the west corner of the range. The result was a “great and apparently architecturally unified palace … uniform in all sorts of ways, as to roof line, window heights, cornice line, floor and ceiling heights”. With the exception of the Hall, Chapel and the Great Chamber, the new interiors all shared a similar height and width. The defensive features, however, were primarily for show, possibly to provide a backdrop for jousting between the two halves of the Order of the Garter.

Edward built further luxurious, self-contained lodgings for his court around the east and south edges of the Upper Ward, creating the modern shape of the quadrangle. The Norman gate was built to secure the west entrance to the Ward. In the Lower Ward, the chapel was enlarged and remodelled with grand buildings for the canons built alongside. The earliest weight-driven mechanical clock in England was installed by Edward III in the Round Tower in 1354. William of Wykeham went on to build New College, Oxford and Winchester College, where the influence of Windsor Castle can easily be seen.

The new castle was used to hold French prisoners taken in at Poitiers in 1357, including John II, who was held for a considerable ransom. Later in the century, the castle also found favour with Richard II. Richard conducted restoration work on St George’s Chapel, the work being carried out by Geoffrey Chaucer, who served as a diplomat and Clerk of The King’s Works.

Windsor Castle continued to be favoured by monarchs in the 15th century, despite England beginning to slip into increasing political violence. Henry IV seized the castle during his coup in 1399, although failing to catch Richard II, who had escaped to London. [98] Under Henry V, the castle hosted a visit from the Holy Roman Emperor in 1417, a massive diplomatic event that stretched the accommodation of the castle to its limits.

By the middle of the 15th century England was increasingly divided between the rival royal factions of the Lancastrians and the Yorkists. Castles such as Windsor did not play a decisive role during the resulting Wars of the Roses (1455–85), which were fought primarily in the form of pitched battles between the rival factions. Henry VI, born at Windsor Castle and known as Henry of Windsor, became king at the young age of nine months. His long period of minority, coupled with the increasing tensions between Henry’s Lancastrian supporters and the Yorkists, distracted attention from Windsor. The Garter Feasts and other ceremonial activities at the castle became more infrequent and less well attended.

Edward IV seized power in 1461. When Edward captured Henry’s wife, Margaret of Anjou, she was brought back to be detained at the castle. [Edward began to revive the Order of the Garter, and held a particularly lavish feast in 1472. Edward began the construction of the present St. George’s Chapel in 1475, resulting in the dismantling of several of the older buildings in the Lower Ward. By building the grand chapel Edward was seeking to show that his new dynasty were the permanent rulers of England, and may also have been attempting to deliberately rival the similar chapel that Henry VI had ordered to be constructed at nearby Eton College. Richard III made only a brief use of Windsor Castle before his defeat at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, but had the body of Henry VI moved from Chertsey Abbey in Surrey to the castle to allow it to be visited by pilgrims more easily.

Henry VII made more use of Windsor. In 1488, shortly after succeeding to the throne, he held a massive feast for the Order of the Garter at the castle. He completed the roof of St George’s Chapel, and set about converting the older eastern Lady Chapel into a proposed shrine to Henry VI, whose canonisation was then considered imminent. In the event, Henry VI was not canonised and the project was abandoned, although the shrine continued to attract a flood of pilgrims. Henry VII appears to have remodelled the King’s Chamber in the palace, and had the roof of the Great Kitchen rebuilt in 1489. He also built a three-storied tower on the west end of the palace, which he used for his personal apartments. Windsor began to be used for international diplomatic events, including the grand visit of Philip I of Castile in 1506. William de la Pole, one of the surviving Yorkists claimants to the throne, was imprisoned at Windsor Castle during Henry’s reign, before his execution in 1513.

Henry VIII enjoyed Windsor Castle, as a young man “exercising himself daily in shooting, singing, dancing, wrestling, casting of the bar, playing the recorders, flute, virginals, in setting of songs and making of ballads”. The tradition of the Garter Feasts was maintained and became more extravagant; the size of the royal retinue visiting Windsor had to be restricted because of the growing numbers. During the Pilgrimage of Grace, a huge uprising in the north of England against Henry’s rule in 1536, the king used Windsor as a secure base in the south from which to manage his military response. Throughout the Tudor period, Windsor was also used as a safe retreat in the event of plagues occurring in London.

Henry rebuilt the principal castle gateway in about 1510 and constructed a tennis court at the base of the motte in the Upper Ward. He also built a long terrace, called the North Wharf, along the outside wall of the Upper Ward; constructed of wood, it was designed to provide a commanding view of the River Thames below. The design included an outside staircase into the king’s apartments, which made the monarch’s life more comfortable at the expense of considerably weakening the castle’s defences. Early in his reign, Henry had given the eastern Lady Chapel to Cardinal Woolsey for Woolsey’s future mausoleum. Benedetto Grazzini converted much of this into an Italian Renaissance design, before Woolsey’s fall from power brought an end to the project, with contemporaries estimating that around £60,000 (£295 million in 2008 terms) had been spent on the work. Henry continued the project, but it remained unfinished when he himself was buried in the chapel, in an elaborate funeral in 1547.

By contrast, the young Edward VI disliked Windsor Castle. Edward’s Protestant beliefs led him to simplify the Garter ceremonies, to discontinue the annual Feast of the Garter at Windsor and to remove any signs of Catholic practices with the Order. During the rebellions and political strife of 1549, Windsor was again used as a safe-haven for the king and the Duke of Somerset. Edward famously commented whilst staying at Windsor Castle during this period that “Methinks I am in a prison, here are no galleries, nor no gardens to walk in”. Under both Edward and his sister, Mary I, some limited building work continued at the castle, in many cases using resources recovered from the English abbeys. Water was piped into the Upper Ward to create a fountain. Mary also expanded the buildings used by the Knights of Windsor in the Lower Ward, using stone from Reading Abbey.

Elizabeth I spent much of her time at Windsor Castle and used it a safe haven in crises, “knowing it could stand a siege if need be”. Ten new brass cannons were purchased for the castle’s defence. It became one of her favourite locations and she spent more money on the property than on any of her other palaces. She conducted some modest building works at Windsor, including a wide range of repairs to the existing structures. She converted the North Wharf into a permanent, huge stone terrace, complete with statues, carvings and an octagonal, outdoor banqueting house, raising the western end of the terrace to provide more privacy. The chapel was refitted with stalls, a gallery and a new ceiling. A bridge was built over the ditch to the south of the castle to enable easier access to the park. Elizabeth built a gallery range of buildings on the west end of the Upper Ward, alongside Henry VII’s tower. Elizabeth increasingly used the castle for diplomatic engagements, but space continued to prove a challenge as the property was simply not as large as the more modern royal palaces. This flow of foreign visitors was captured for the queen’s entertainment in William Shakespeare’s play, The Merry Wives of Windsor.

James I used Windsor Castle primarily as a base for hunting, one of his favourite pursuits, and for socialising with his friends. Many of these occasions involved extensive drinking sessions, including one with Christian IV of Denmark in 1606 that became infamous across Europe for the resulting drunken behaviour of the two kings. The absence of space at Windsor continued to prove problematic, with James’ English and Scottish retinues often quarrelling over rooms.

Charles I was a connoisseur of art, and paid greater attention to the aesthetic aspects of Windsor Castle than his predecessors. Charles had the castle completely surveyed by a team including Inigo Jones in 1629, but little of the recommended work was carried out. Nonetheless, Charles employed Nicholas Stone to improve the chapel gallery in the Mannerist style and to construct a gateway in the North Terrace. Christian van Vianen, a noted Dutch goldsmith, was employed to produce a baroque gold service for the St George’s Chapel altar. In the final years of peace, Charles demolished the fountain in the Upper Ward, intending to replace it with a classical statue.

In 1642 the English Civil War broke out, dividing the country into the Royalist supporters of Charles, and the Parliamentarians. In the aftermath of the battle of Edgehill in October, Parliament became concerned that Charles might advance on London. John Venn took control of Windsor Castle with twelve companies of foot soldiers to protect the route along the Thames River, becoming the governor of the castle for the duration of the war. The contents of St George’s Chapel were both valuable and, to many Parliamentary forces, inappropriately high church in style. Looting began immediately: Edward IV’s bejewelled coat of mail was stolen; the chapel’s organs, windows and books destroyed; the Lady Chapel was emptied of valuables, including the component parts of Henry VIII’s unfinished tomb. By the end of the war, some 3580 oz (101 kg) of gold and silver plate had been looted.

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, a prominent Royalist general, attempted to relieve Windsor Castle that November. Rupert’s small force of cavalry was able to take the town of Windsor, but was unable to overcome the walls at Windsor Castle – in due course, Rupert was forced to retreat. Over the winter of 1642–3, Windsor Castle was converted into the headquarters for the Earl of Essex, a senior Parliamentary general. The Horseshoe Cloister was taken over as a prison for captured Royalists, and the resident canons were expelled from the castle. The Lady Chapel was turned into a magazine. Looting by the underpaid garrison continued to be a problem; 500 royal deer were killed across the Windsor Great Park during the winter, and fences were burned as firewood.

In 1647 Charles, then a prisoner of Parliament was brought to the castle for a period under arrest, before being moved to Hampton Court. In 1648 there was a Royalist plan, never enacted, to seize Windsor Castle. The Parliamentary Army Council moved into Windsor in November and decided to try Charles for treason. Charles was held at Windsor again for the last three weeks of his reign; after his execution in January 1649, his body was taken back to Windsor that night through a snowstorm, to be interred without ceremony in the vault beneath St George’s Chapel.

The Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 saw the first period of significant change to Windsor Castle for many years. The civil war and the years of the Interregnum had caused extensive damage to the royal palaces in England. At the same time the shifting “functional requirements, patterns of movement, modes of transport, aesthetic taste and standards of comfort” amongst royal circles was changing the qualities being sought in a successful palace. Windsor was the only royal palace to be successfully fully modernised by Charles II in the Restoration years.

During the Interregnum, however, squatters had occupied Windsor Castle. As a result, the “King’s house was a wreck; the fanatic, the pilferer, and the squatter, having been at work … Paupers had squatted in many of the towers and cabinets”. Shortly after returning to England, Charles appointed Prince Rupert, one of his few surviving close relatives, to be the Constable of Windsor Castle in 1668. Rupert immediately began to reorder the castle’s defences, repairing the Round Tower and reconstructing the real tennis court. Charles attempted to restock Windsor Great Park with deer brought over from Germany, but the herds never recovered their pre-war size. Rupert created apartments for himself in the Round Tower, decorated with an “extraordinary” number of weapons and armour, with his inner chambers “hung with tapisserie, curious and effeminate pictures”.

Charles was heavily influenced by the works of Louis XIV of France, imitating French design at his palace at Winchester and the Royal Hospital at Chelsea. At Windsor, Charles created “the most extravagantly Baroque interiors ever executed in England”. Much of the building work was paid for out of increased royal revenues from Ireland during the 1670s. French court etiquette at the time required a substantial number of enfiladed rooms in order to satisfy court protocol; the demand for space forced May to expand out into the North Terrace, rebuilding and widening it in the process This new building was called the Star Building, because Charles II placed a huge gilt Garter star on the side of it. May took down and rebuilt the walls of Edward III’s hall and chapel, incorporating larger windows but retaining the height and dimensions of the medieval building. Although Windsor Castle was now big enough to hold the entire court, it was not built with chambers for the King’s Council, as would be found in Whitehall. Instead Charles took advantage of the good road links emerging around Windsor to hold his council meetings at Hampton Court when he was staying at the castle. The result became an “exemplar” for royal buildings for the next twenty-five years. The result of May’s work showed a medievalist leaning; although sometimes criticised for its “dullness”, May’s reconstruction was both sympathetic to the existing castle and a deliberate attempt to create a slightly austere 17th-century version of a “neo-Norman” castle.

William III commissioned Nicholas Hawksmoor and Sir Christopher Wren to conduct a large, final classical remodelling of the Upper Ward, but the king’s early death caused the plan to be cancelled. Queen Anne was fond of the castle, and attempted to address the lack of a formal garden by instructing Henry Wise to begin work on the Maestricht Garden beneath the North Terrace, which was never completed. Anne also created the racecourse at Ascot and began the tradition of the annual Royal Ascot procession from the castle.

George I took little interest in Windsor Castle, preferring his other palaces at St James’s, Hampton Court and Kensington. George II rarely used Windsor either, preferring Hampton Court. Many of the apartments in the Upper Ward were given out as “grace and favour” privileges for the use of prominent widows or other friends of the Crown. The Duke of Cumberland made the most use of the property in his role as the Ranger of Windsor Great Park. By the 1740s, Windsor Castle had become an early tourist attraction; wealthier visitors who could afford to pay the castle keeper could enter, see curiosities such as the castle’s narwhal horn, and by the 1750s buy the first guidebooks to Windsor, produced by George Bickham in 1753 and Joseph Pote in 1755. As the condition of the State Apartments continued to deteriorate, even the general public were able to regularly visit the property.

George III reversed this trend when he came to the throne in 1760. George disliked Hampton Court, and was attracted by the park at Windsor Castle. George wanted to move into the Ranger’s House by the castle, but his brother, Henry was already living in it and refused to move out. Instead, George had to move into the Upper Lodge, later called the Queen’s Lodge, and started the long process of renovating the castle and the surrounding parks. Initially the atmosphere at the castle remained very informal, with local children playing games inside the Upper and Lower Wards, and the royal family frequently seen as they walked around the grounds. As time went by, however, access for visitors became more limited.

George’s architectural taste shifted over the years. As a young man, he favoured Classical, in particular Palladian styles, but the king came to favour a more Gothic style, both as a consequence of the Palladian style becoming overused and poorly implemented, and because the Gothic form had come to be seen as a more honest, national style of English design in the light of the French revolution. Working with the architect James Wyatt, George attempted to “transform the exterior of the buildings in the Upper Ward into a Gothic palace, while retaining the character of the Hugh May state rooms”. The outside of the building was restyled with Gothic features, including new battlements and turrets Inside, conservation work was undertaken, and several new rooms constructed, including a new Gothic staircase to replace May’s 17th-century version, complete with the Grand Vestibule ceiling above it. New paintings were purchased for the castle, and collections from other royal palaces moved there by the king. The cost of the work came to over £150,000 (£100 million in 2008 terms). The king undertook extensive work in the castle’s Great Park as well, laying out the new Norfolk and Flemish farms, creating two dairies and restoring the Virginia Water lake, grotto and follies.

At the end of this period Windsor Castle became a place of royal confinement. In 1788 the king first became ill during a dinner at Windsor Castle; diagnosed as suffering from madness, he was removed for a period to Kew, where he temporarily recovered. After relapses in 1801 and 1804, his condition became enduring from 1810 onwards and he was confined in the State Apartments of Windsor Castle, with building work on the castle ceasing the following year.

George IV came to the throne in 1820 intending to create a set of royal palaces that reflected his wealth and influence as the ruler of an increasingly powerful Britain. George’s previous houses, Carlton House and the Brighton Pavilion were too small for grand court events, even after expensive extensions. George expanded the Royal Lodge in the castle park whilst he was Prince Regent, and then began a programme of work to modernise the castle itself once he became king.

George persuaded Parliament to vote him £300,000 for restoration (£245 million in 2008 terms). Under the guidance of George’s advisor, Charles Long, the architect Jeffry Wyattville was selected, and work commenced in 1824. Wyattville’s own preference ran to Gothic architecture, but George, who had led the reintroduction of the French Rococo style to England at Carlton House, preferred a blend of periods and styles, and applied this taste to Windsor. The terraces were closed off to visitors for greater privacy and the exterior of the Upper Ward was completely remodelled into its current appearance. The Round Tower was raised in height to create a more dramatic appearance; many of the rooms in the State Apartments were rebuilt or remodelled; numerous new towers were created, much higher than the older versions. The south range of the ward was rebuilt to provide private accommodation for the king, away from the state rooms. The statue of Charles II was moved from the centre of the Upper Ward to the base of the motte. Sir Walter Scott captured contemporary views when he noted that the work showed “a great deal of taste and feeling for the Gothic architecture”; many modern commentators, including Prince Charles, have criticised Wyattville’s work as representing an act of vandalism of May’s earlier designs. The work was unfinished at the time of George IV’s death in 1830, but was broadly completed by Wyattville’s death in 1840. The total expenditure on the castle had soared to the colossal sum of over one million pounds (£817 million in 2008 terms) by the end of the project.

A black and white photograph of an elderly Victoria sat alongside a younger woman (Beatrice) reading a newspaper. The room is ornately decorated, with a number of photographs, paintings and a large chandelier hanging from the ceiling.

Queen Victoria and Princess Beatrice in the Queen’s Sitting Room in 1895, photographed by Mary Steen

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert made Windsor Castle their principal royal residence, despite Victoria complaining early in her reign that the castle was “dull and tiresome” and “prison-like”, and preferring Osborne and Balmoral as holiday residences. The growth of the British Empire and Victoria’s close dynastic ties to Europe made Windsor the hub for many diplomatic and state visits, assisted by the new railways and steamships of the period. Indeed, it has been argued that Windsor reached its social peak during the Victorian era, seeing the introduction of invitations to numerous prominent figures to “dine and sleep” at the castle. Victoria took a close interest in the details of how Windsor Castle was run, including the minutiae of the social events. Few visitors found these occasions comfortable, both due to the design of the castle and the excessive royal formality. Prince Albert died in the Blue Room at Windsor Castle in 1861 and was buried in the Royal Mausoleum built at nearby Frogmore, within the Home Park. The prince’s rooms were maintained exactly as they had been at the moment of his death and Victoria kept the castle in a state of mourning for many years, becoming known as the “Widow of Windsor”, a phrase popularised in the famous poem by Rudyard Kipling. The Queen shunned the use of Buckingham Palace after Albert’s death and instead used Windsor Castle as her residence when conducting official business near London. Towards the end of her reign plays, operas and other entertainments slowly began to be held at the castle again, accommodating both the Queen’s desire for entertainment and her reluctance to be seen in public.

Several minor alterations were made to the Upper Ward under Victoria. Anthony Salvin rebuilt Wyattville’s grand staircase, with Edward Blore constructing a new private chapel within the State Apartments. Salvin also rebuilt the State Dining Room following a serious fire in 1853. Ludwig Gruner assisted in the design of the Queen’s Private Audience Chamber in the south range. Blore and Salvin also did extensive work in the Lower Ward, under the direction of Prince Albert, including the Hundred Steps leading down into Windsor town, rebuilding the Garter, Curfew and Salisbury towers, the houses of the Military Knights and creating a new Guardhouse. George Gilbert Scott rebuilt the Horseshoe Cloister in the 1870s. The Norman Gatehouse was turned into a private dwelling for Sir Henry Ponsonby. Windsor Castle did not benefit from many of the minor improvements of the era, however, as Victoria disliked gaslight, preferring candles; electric lighting was only installed in limited parts of the castle at the end of her reign. Indeed, the castle was famously cold and draughty in Victoria’s reign, but it was connected to a nearby reservoir, with water reliably piped into the interior for the first time.

Many of the changes under Victoria were to the surrounding parklands and buildings. The Royal Dairy at Frogmore was rebuilt in a Tudorbethan style in 1853; George III’s Dairy rebuilt in a Renaissance style in 1859; the Georgian Flemish Farm rebuilt, and the Norfolk Farm renovated. The Long Walk was planted with fresh trees to replace the diseased stock. The Windsor Castle and Town Approaches Act, passed by Parliament in 1848, permitted the closing and re-routing of the old roads which previously ran through the park from Windsor to Datchet and Old Windsor. These changes allowed the Royal Family to undertake the enclosure of a large area of parkland to form the private “Home Park” with no public roads passing through it. The Queen granted additional rights for public access to the remainder of the park as part of this arrangement.

Edward VII came to the throne in 1901 and immediately set about modernising Windsor Castle with “enthusiasm and zest”. Many of the rooms in the Upper Ward were de-cluttered and redecorated for the first time in many years, with Edward “peering into cabinets; ransacking drawers; clearing rooms formerly used by the Prince Consort and not touched since his death; dispatching case-loads of relics and ornaments to a special room in the Round Tower … destroying statues and busts of John Brown … throwing out hundreds of ‘rubbishy old coloured photographs’ … [and] rearranging pictures”. Electric lighting was added to more rooms, along with central heating; telephone lines were installed, along with garages for the newly invented automobiles. The marathon was run from Windsor Castle at the 1908 Olympics, and in 1911 the pioneering aviator Thomas Sopwith landed an aircraft at the castle for the first time.

George V continued a process of more gradual modernisation, assisted by his wife, Mary of Teck, who had a strong interest in furniture and decoration. Mary sought out and re-acquired items of furniture that had been lost or sold from the castle, including many dispersed by Edward VII, and also acquired many new works of art to furnish the state rooms. Queen Mary was also a lover of all things miniature, and a famous dolls’ house was created for her at Windsor Castle, designed by the architect Edwin Lutyens and furnished by leading craftsmen and designers of the 1930s. George V was committed to maintaining a high standard of court life at Windsor Castle, adopting the motto that everything was to be “of the best”. A large amount of staff was still kept at the castle, with around 660 servants working in the property during the period. Meanwhile, during the First World War, anti-German feeling led the members of the Royal Family to change their dynastic name from the German House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; George decided to take the new name from the castle, and the Royal Family became the House of Windsor in 1917.

Edward VIII did not spend much of his reign at Windsor Castle. He continued to spend most of his time at Fort Belvedere in the Great Park, where he had lived whilst Prince of Wales. Edward created a small aerodrome at the castle on Smith’s Lawn, now used as a golf-course. Edward’s reign was short-lived and he broadcast his abdication speech to the British Empire from the castle in December 1936, adopting the title of Duke of Windsor. His successor, George VI also preferred his own original home, the Royal Lodge in the Great Park, but moved into Windsor Castle with his wife Elizabeth. As king, George revived the annual Garter Service at Windsor, drawing on the accounts of the 17th-century ceremonies recorded by Elias Ashmole, but moving the event to Ascot Week in June.

On the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 the castle was readied for war-time conditions. Many of the staff from Buckingham Palace was moved to Windsor for safety, security was tightened and windows were blacked-out. There was significant concern that the castle might be damaged or destroyed during the war; the more important art works were removed from the castle for safe-keeping, the valuable chandeliers were lowered to the floor in case of bomb damage and a sequence of paintings by John Piper were commissioned from 1942–4 to record the castle’s appearance. The king and queen and their children Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret lived for safety in the castle, with the roof above their rooms specially strengthened in case of attack. The king and queen drove daily to London, returning to Windsor to sleep, although at the time this was a well-kept secret, as for propaganda and morale purposes it was reported that the king was still residing full-time at Buckingham Palace. After the war the king revived the “dine and sleep” events at Windsor, following comments that the castle had become “almost like a vast, empty museum”; nonetheless, it took many years to restore Windsor Castle to its pre-war condition.

In February 1952, Elizabeth II came to the throne and decided to make Windsor her principal weekend retreat. The private apartments which had not been properly occupied since the era of Queen Mary were renovated and further modernised, and the Queen, Prince Philip and their two children took up residence. By the early 1990s, however, there had been a marked deterioration in the quality of the Upper Ward, in particular the State Apartments. Generations of repairs and replacements had resulted in a “diminution of the richness with which they had first been decorated”, a “gradual attrition of the original vibrancy of effect, as each change repeated a more faded version of the last”. A programme of repair work to replace the heating and the wiring of the Upper Ward began in 1988.] Work was also undertaken to underpin the motte of the Round Tower after fresh subsidence was detected in 1988, threatening the collapse of the tower.